Out of Antarctica.

For 21 nights, 22 days, I lived on a ship that took me to Antarctica – one of the most remote and inhospitable places on earth. Antarctica conjures up the capriciousness of polar extremes, romanticism of the period of great polar expeditions, and images of ice shelves breaking and forming which create important habitat for the Antarctic fauna. Antarctica is this and so much more. Antarctica changes people.

In essence, this adventure began almost a year ago when I was selected as 1 of 78 international women in Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) for a unique leadership program, which culminated in this expedition. It is well documented that Women in STEM are under-represented in leadership. The vision of Homeward Bound is to increase leadership capacity and visibility of women in STEM and to build a 1000-strong network and collaboration of women to influence decision-making and policy on important environmental issues, including climate change, as it impacts the future of our planet.

Antarctica was chosen for a reason – it’s not an easy continent to get to. It is remote and will challenge you in unexpected ways. As I boarded the ship in Ushuaia, Argentina, I was full of excitement and expectation with little idea of how I would be tested.

The ship, our home for the duration of the expedition, was built in the 1970s as a research vessel for the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It is a small ship by comparison to other vessels that sail the Drake Passage with a capacity of only 90 passengers. It does not have stabilizers as many of the more modern ships do, so even the calmest of seas are felt. Someone had likened it to a cork bobbing at will in the sea, which proved to be a fairly apt description.

To reach Antarctica from Ushuaia, you must first cross the Drake Passage, a body of water that connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean with the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean and extends into the Southern Ocean. The Drake Passage is notoriously difficult. There is an old mariner’s quote that says “below 40 degrees south there is no law; below 50 degrees south there is no God”.

Recognizing that it might be a difficult passage, the ship’s physician, who had a no-nonsense demeanor, basically anesthetized us with medications she passed around on the first night onboard. I spent much of the passage bemoaning the fact I had not thought through the ship portion of this adventure thoroughly.

Life onboard ship.

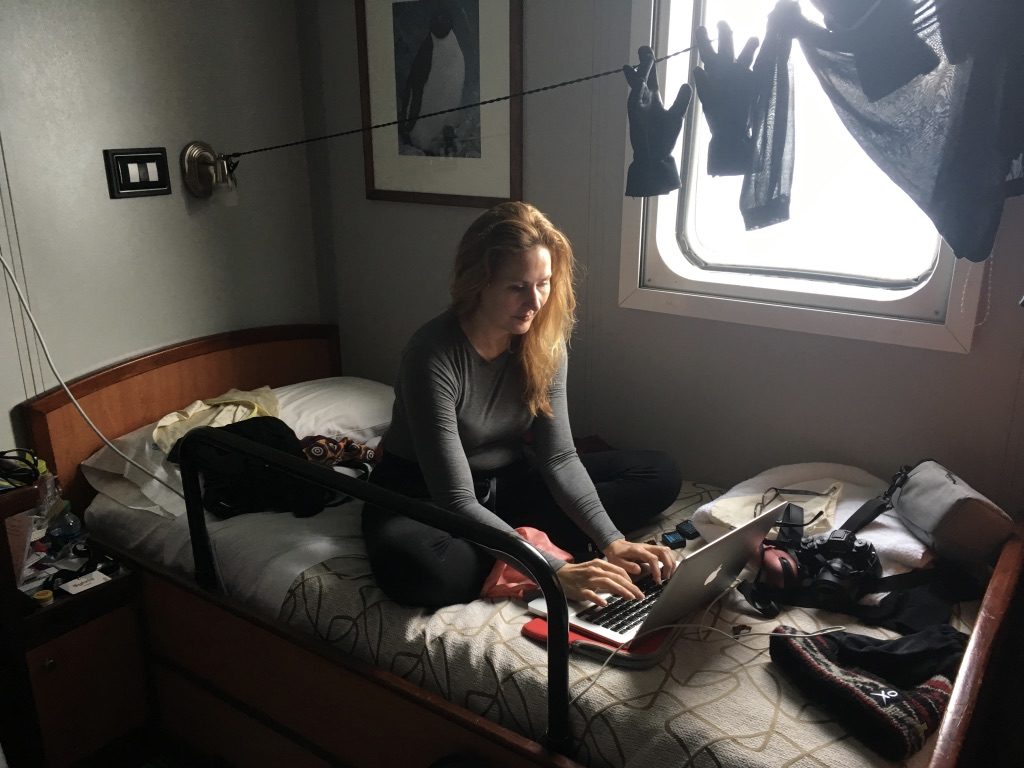

Our little vessel had three tiers of accommodation, all of which were shared. There was a top, middle, and bottom tier accommodation. In the spirit of fairness, we all switched cabins and cabin-mates mid-trip. Because I had been in the top tier, I got to see opposite end of the spectrum for the second half of the voyage.

The top tier consisted of a relatively spacious upstairs cabin with beds, bedside tables, desk, a relatively large window and attached shower, which was quite comfortable. By contrast, the bottom tier was accessed via stairwell to the bowels of the boat, which reeked of diesel fumes. The lower cabin was outfitted with bunk beds that felt claustrophobic, a desk, porthole and a shower and toilet that is shared between cabins (4 people). The upside of being assigned to the bottom tier is that I spent more time outside my cabin getting to know my fellow shipmates.

“Good morning possums.”

Each morning we were greeted by a wake up announcement with Greg Mortimer channeling Dame Edna over the ship’s intercom system. Greg Mortimer, our expedition leader, is an exceptional person by anyone’s standard not only for his many incredible exploits, but because of his warmth, intelligence, and curiosity. I asked him what drew him basically out of retirement to be the expedition leader and he mentioned that he was in awe of the women that participated in the expedition and the spirit of collaboration that existed among the participants. It made him feel optimistic about the future. That resonated deeply with me because I too feel that with my fellow participants – the intelligence, experience, collaborative spirit, and passion – we can create a better and more sustainable future.

Increasing leadership capacity and understanding.

While aspects of the leadership program were delivered in the year prior to arriving in Ushuaia, the bulk of the program was delivered during the initial days in Ushuaia and onboard ship. Part of the leadership learning was employing tools to better understand individual strengths, developing strategies, developing peer-coaching skills, and understanding and employing 4-mat to more effectively communicate ideas.

The 4-mat process divides how we learn and communicate into four quadrants – why, what, how and if. Prior to boarding ship, all of the participants took an assessment to determine their preferences. By knowing where you fall on each of the quadrant gradients, you are able to better understand your own tendencies as well as broaden the way you communicate. By ensuring the inclusion of other quadrants, one is able to communicate more effectively to diverse audiences.

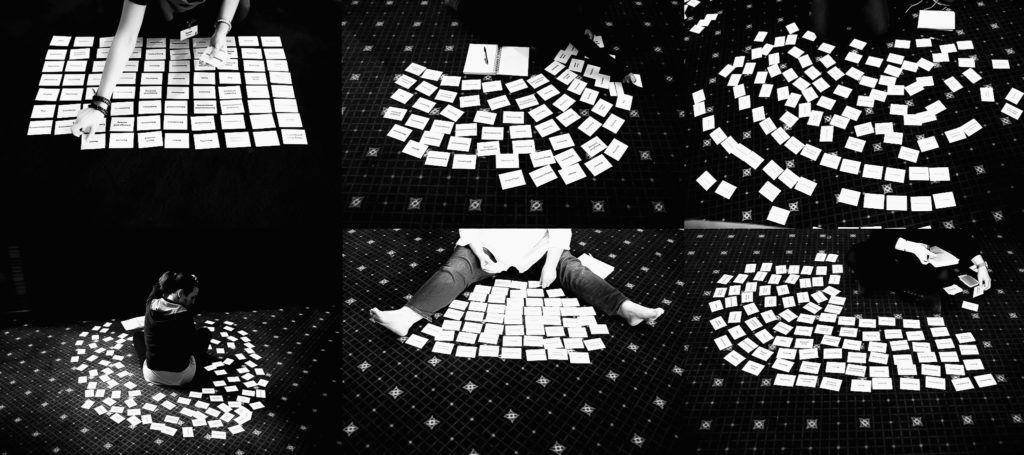

While we were still in Ushuaia, we were given decks of cards with values and asked to select 10 that resonated with us. We then sorted the cards by comparing pairs of values to ultimately select our top three for each of our strategy streams – work, relationships and self. These values formed the basis of developing personal strategy maps that incorporated these values. By identifying core values, you are more able to ground yourself and leadership strategy that incorporates these values. The personal strategy map also provides a framework to bring together learning from the program and to make conscious choices that align with these values.

Visibility and science communication is another important aspect of the leadership training we received onboard ship. As part of the visibility and science communication stream, we learned to create a narrative around our professional and personal goals and to align this with our personal strategy. We were asked to create a 100-day plan and develop actionable goals. I noticed that while the participants are highly accomplished and noted experts in their fields, they often do not seek out visibility. I believe that when more people see the amazing things that women are accomplishing, people will start changing their minds about what is possible and encouraging more women to get into STEM.

Onboard ship, each of us delivered a 3-minute speech to introduce what we do for symposium@sea, in the 4-mat styles of communication. While we were beginning to get to know each other socially, the symposium@sea gave us an opportunity to connect with one another on the breadth and depth of knowledge and expertise in the room for future collaboration and networking.

Another one of our tasks was to provide a talk on an important environmental topic as teams. Prior to boarding the ship, we had self-selected into participant-identified important global environmental issues. Topics included water scarcity and health, plastic pollution, alternative energy, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and climate change science and impacts to increase our collective understanding and knowledge on these important issues. Because of the work I do on water issues with one of the indigenous groups in Canada (First Nations), I self-selected into water scarcity and health group which then further split into freshwater and oceans based on the groups interest and expertise.

To incorporate different communications styles, part of the presentation on water scarcity and health was delivered via a game where participants were asked to match a statement of water-related information with the correct country or region. The aim is to further develop and expand this game as a teaching tool for schools and students of varying ages.

Members of the Homeward Bound leadership team included noted experts conducting research on Antarctic flora, fauna, benthic organisms, and climate change impacts. These experts provided lectures to increase our understanding of the unique and fragile ecosystem of Antarctica. Other science and leadership lectures were delivered via filmed faculty by noted women scientists and leaders who had donated their time to Homeward Bound. These included noted primatologist Dr. Jane Goodall, noted marine biologist and conservationist Dr. Sylvia Earl, and internationally recognized leader on climate change Christiana Figueres among others.

Off the ship and onto Antarctica.

When we were not in the ship’s lounge (the most spacious area on the ship) learning about leadership, each other’s expertise, and Antarctica, we were preparing to board the zodiacs to take us to the coastal islands or peninsula of Antarctica.

Prior to our first landing, we were briefed on the International Antarctic Treaty Organization (IAATO), which governs Antarctica. Antarctica is unique in that it is the only continent without an indigenous population and an international agreement to designate the entire continent as “a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science.” As part of the treaty, there is a protocol that sets standards for human activities to reduce any foreign materials or species to Antarctica. The briefing included procedures for cleaning and disinfecting the rubber boots we were given for the duration of the voyage, prior to and after landing, to reduce contamination.

Our first landing was on Halfmoon Bay, an island that is part of the South Shetlands just north of the Antarctic Peninsula. As preparation for the landing, we were given a scientific briefing about the seabirds and penguin species we would see on the island.

The island is inhabited by chinstrap penguins, named for their remarkable facial markings, and seals. (Other areas visited during the expedition had other species of penguin such as Gentoo and Adélie, which inhabit slightly different niches). Penguins are rather comical on land as they waddle from side to side. Many of the penguins we saw throughout the expedition were chicks that were waiting for their adult feathers to come in and provide the water-proofing necessary to venture into the water to feed. Their various stages of molting provided some humorous looking ‘hairdos’.

At various points along the voyage, we made stops to explore the incredible landscapes of Antarctica and to visit research bases that were dotted along the route of the expedition. These included Camara (AR), Carlini (AR), Great Wall (China), Palmer (US), Rothera (UK). As scientists, visiting the research bases was both a privilege and a unique opportunity to engage with the researchers working in Antarctica and obtain insights into their work and the day-to-day life on the base.

Much of the research discussed at each of the research stations dealt with species in the marine environment and possible medicinal benefits or changes due to climate change. We experienced quite a bit of rain at the beginning of our expedition, which I was told was highly unusual. The climate is changing and there is research to back this up.

During most of our visits, we were shown around the base by the commander or a member of the research team. The Great Wall Research Station (China), was an exception; we were kept to a fairly restricted area with base personnel ensuring that our group did not stray (there was a high risk in straying because we are scientists and inquisitive by nature). There was a bit of a language barrier but because a few of the participants were Chinese, we were able to get some information from the brief exchanges with the personnel that were stationed there to keep us from straying. While the personnel at the Great Wall station were cordial, this visit’s restricted nature was unusual. The researchers and personnel at other research stations fully engaged with us, gave us greater access and welcomed our questions.

Our arrival at the bases coincided with the end of summer (late March) season just as the bases were gearing up for a change in personnel for the Antarctic winter. One gets the impression that they are a tight knit group, partially out of necessity as the long, cold, sunless winter sets in.

Travel to Rothera.

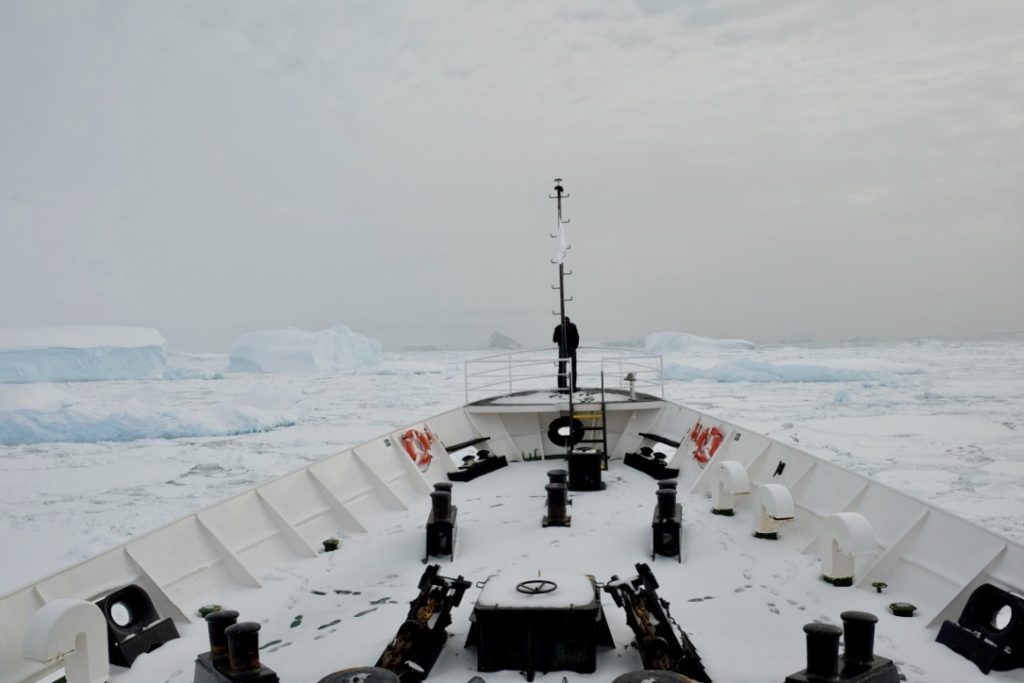

The last research base we were able to visit was Rothera, which is farther south than most non-governmental ships venture (below the polar circle, station location is Lat. 67°35’8″S). In fact, the station only allows two non-governmental ships to visit a year and ours was selected because of the women researchers and scientists onboard. Rothera is difficult to get to due to the sea ice conditions, which often inhibits ships that are not classed as icebreakers from getting through. We later learned we were the only non-governmental ship to make it and were the last ones for the next 2-3 years while the docking area undergoes refurbishment.

Getting to Rothera proved to be an emotional and physical strain. A number of the participants were highly sensitive to motion sickness (myself included), so there was a discussion as to whether or not to make the attempt since the sea ice would likely necessitate making the voyage through open sea. We held a blind vote and it was initially decided to not make the attempt. The leadership team had decided to act with empathy and in solidarity with those who were anxious about the anticipated nausea that would be induced by the roughness of the open sea.

While I am one of those highly sensitive people, I had still voted to forge ahead knowing that the likelihood of making it again would be slim. The mood on the ship was subdued as we processed the information. The next day, however, there was a reversal of the decision since more information on sea conditions had come to light. The captain and a number of crew had not ventured this far south and were keen to push on since this is the only time during the season (late summer) when the sea ice is relatively thin and this could be attempted.

Pushing through the sea ice was a surreal experience. There was a calmness despite the loud cracks and scraping noise against the bow as the ship plowed slowly through the sea ice. Progress was very slow as we pushed our way south. One of the crew from the bridge was stationed on the bow to provide regular updates to the captain to ensure we would not be in peril from the sea ice. As soon as we had forged ahead a little way, the ice would close quickly from behind enveloping the ship in whiteness.

The austere seascape was broken up by sightings of seals whose dark shapes dotted the sheets of sea ice. Sea ice provides important habitat for the seals and penguins during the winter months in Antarctic. Most of us lingered on deck, despite the cold, to watch as the Ushuaia made its way through the sea ice. As we broke through the sea ice and into open water, the scenery changed to reveal calm water mirroring majestic icebergs.

Icebergs can easily be thousands of years old and have a never-ending array of shapes, textures and colors. They are fascinating and beautiful to watch; as we slowly passed by, other angles and surfaces of the icebergs were revealed. It is hard to believe that these monolithic giants show only ten percent of their actual mass above water.

After Rothera, we began our voyage north back to Ushuaia making additional stops along the way including Neko Harbour. At Neko Harbour, we were able to sit quietly among the gentoo penguin chicks and watch their antics. The chicks chased hapless adults for food and the adults foraged for krill – their main food source – in the shallow waters in front of the beach. Neko Harbour marked the end of the snowy landscape before the change to the post-apocalyptic landscape of Deception Island.

Deception Island

Deception Island has an ominous name and an even more forbidding landscape. Signs of human habitation can be seen from a long since defunct whaling station. The last eruption in the 1960s coated the island in a dark volcanic rock that creates a beautiful but eerie contrast to snow that settles into the folds of the landscape. Adding to the eeriness, beaches steam from where the heated waters from the geothermal activity meet the cold Antarctic waters. In some ways, this was a perfect last visit, which brought home the fragility of Antarctic region and its stark beauty.

The journey back across the Drake Passage was relatively calm and despite this, seabirds and land were a welcome site. I can imagine it was a welcome site to seafarers of earlier days that had to contend with much harsher conditions due to lack of technologies and comforts to which we had access.

There is so much to process on a trip such as this; the stark beauty of the Antarctic desert, the power of the weather and ice, its vastness and stillness, its vulnerability and fragility which stirs a desire to protect. It changes you in unexpected ways some of which I am still reflecting on and continuing to learn from the experience of the journey.

Even though I have returned to where I live, the journey has not yet ended.

Epilogue

This story is also being told through other mediums as well. Samantha Hodden was podcaster in residence during the voyage. She will be sharing stories through her podcast This is Our Time. Oli Sansom joined the expedition as the photographer on board to capture the voyage. He will be producing a photography book about the expedition. In addition to this blog post, I have put together a short youtube video to share the experience.